Is Product Sense Overrated?

First, let’s try to define product sense.

Jackie Bavaro defines product sense as:

Product Sense (also called Product Intuition or Product Judgement) is the ability to understand what makes a product great. It’s the ability to hone in on the important problems a product solves and come up with ideas to make it even better.

More from Jackie here in this great Twitter thread.

Lenny Rachitsky describes great product sense as:

And Shreyas Doshi defines it as:

The ability to usually make correct product decisions even when there is significant ambiguity.

I think it’s important to define sense as well. There are multiple definitions of sense.

From Merriam-Webster dictionary I think the best fit here for sense is:

A capacity for effective application of the powers of the mind as a basis for action or response

To synthesize these we can say that product sense is the capacity to make decisions based on knowledge and understanding of what makes a great product for your users.

I don’t think we can use the qualifier “correct” for these decisions because in doing so we have survivorship bias for only the products that succeeded when an otherwise sound product decision was made but some other, external factor caused the product to fail.

Ok. What’s the definition of ‘gut feeling’?

From the free dictionary:

An intuition or instinct, as opposed to an opinion based on a logical analysis.

Based on these definitions, I don’t think product sense and gut feeling are the same things. However, when we rely on our product sense it’s usually because data is limited and so we have no choice but to rely on our instincts to make a decision.

Product sense is not scaleable

"The problem with 'gut feel' is that it's not repeatable. You can't test it, you can't prove it, and you can't improve upon it." - Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Let me try to illustrate the problem of relying on product sense alone through a sports analogy.

What if we applied this definition of product sense to another kind of evaluation, say player evaluation? We might have a definition that reads like this:

Having a ‘sharp eye for talent’ is the ability to identify great players based on knowledge and understanding of what makes a great player.

Could a baseball team win by constructing a roster based solely on their scouts’ ‘sharp eye for talent’? What would that look like? Selecting players based on their physical appearance? Or perceived skill? Possibly based on their potential? Or maybe some other intangibles like culture fit and work ethic?

Well, this was basically how recruiting in all of the major sports was done prior to the adoption of advanced analytics. That’s not to say it can’t work. But this approach alone takes on a large amount of risk.

Data changes the game

But what if there was a way we could limit risk and produce a higher ROI?

In his 2003 book "Moneyball," Michael Lewis presents a critical analysis of the methodology employed by baseball scouts, emphasizing their over-reliance on subjective and anecdotal information in contrast to objective data and analysis. He argues that traditional scouting practices often result in decisions based on a player's physical appearance and perceived potential rather than their actual performance on the field. Almost like using only that ‘sharp eye for talent’ (i.e. product sense) for evaluating baseball players.

In comes Billy Beane as general manager of the Oakland A's and with him sabermetrics, a statistical analysis of baseball data, to identify undervalued players and construct a winning team on a budget. The use of advanced analytics indeed changed the way scouting, strategy, and roster construction are done not only in Major League Baseball but in other sports leagues as well.

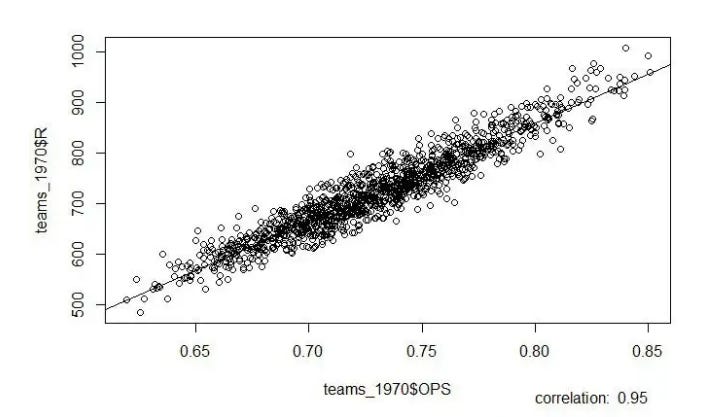

Figure 1 shows the high correlation between on-base percentage + slugging and runs

The Moneyball era and the analytics revolution that swept through sports highlighted that sense alone was not enough to get the biggest bang for your buck. Sure, rich teams could and did spend their way to wins. Kind of like big tech companies do. But that’s not a playbook that can work for all PMs, everywhere.

Analogy caveats

There are of course differences in the contexts in which a GM of a baseball team and a product manager make decisions. In fact, I believe there is more ambiguity in product management than there is in managing a baseball team! Also, metrics aren’t perfect, but they can be improved and we can measure if they indeed have improved. Another important note is that data does not necessarily equal insights. Prior to sabermetrics, metrics like batting average, runs batted in, and steals were used to measure player performance. These have been shown to be less correlated to performance than once thought. This would be like a product manager using vanity metrics to measure success. (Moneyball is secretly a product management book).

Pitfalls of over-reliance on product sense

I think that the significance of product sense to making an impact as a PM is overemphasized and not provable. While product sense can be learned and refined, it can’t be measured. This is its biggest flaw.

That’s not to say it doesn’t have its place in the toolbox of a high-performing product manager. However, PMs should understand the pitfalls of relying on product sense alone when making decisions. These include:

Bias: Product managers may be more susceptible to biases, such as confirmation bias.

Lack of objectivity: Relying too heavily on product sense can lead to a lack of objectivity in decision-making, as decisions may be based on a subjective understanding of the market and user needs rather than data, research, and analysis.

Limited perspective: Product managers may be limited to their own perspectives and overlook the perspectives of other stakeholders.

Inability to measure or improve: Without data product managers may find it difficult to measure or improve their decisions.

Inability to scale: Scaling decision-making may be challenging without data.

Product sense as a filter

In the first edition of this newsletter, I shared that I am currently working as a product manager for sports data collection software. Generally, my goal is for the product to enable data collectors to collect the highest quality data, fast. I am fortunate to be able to understand the impact of my work from performance metrics as well as from continuous qualitative feedback from data collectors. I’m even able to observe their behavior at length.

When it comes to problem discovery I can’t make excuses about not knowing what my user needs.

I know product managers have varying degrees of data about their markets and users but I do believe that in most cases of product work, product managers have enough data to make data-informed decisions about what their users need.

I’ve found that, even with data, product sense is most valuable as a filter in solution discovery. Having high product sense helps a product manager make quick decisions about solutions as they have a detailed understanding of not only how their product works, but technology in general. This is the first level of assumption testing and is a real time saver.

When should you rely on product sense to make a decision?

If your situation has a high amount of ambiguity, you may have to lean more on your product sense to make decisions.

In fast-changing or uncertain markets, a product manager with a strong product sense, who can quickly identify new opportunities and respond to market changes, may be more effective. Similarly, when developing a new product or entering a new market, there may be limited data available. In these situations, a product manager will have to draw from the well of previous experience for guidance.

The key takeaway here is, like a baseball GM, product managers need to use their product sense as a compliment to being data-informed. This is why I think the ability to understand what metrics are important and measure them is what separates great PMs from the pack. More so than product sense.